A reader recently asked me to explain the title of the newsletter. I thought that venture might be a good place to start.

Let me first affirm that the title is an obvious play on “eminent domain.” Don’t worry. I won’t write a word on government claims to private property.

OK, let’s begin.

This … Domain

I am using “This … Domain” to represent the physical, the material, the carbon-based world that we exist within and are a part of as physical beings. It is the thing or things we can measure with instruments, quantify with equations, and map with charts.

It is the “whatness” of the world that we attempt to understand, acquire, and possess.

For instance, we can scientifically categorize trees into the coniferous and deciduous. Roughly, coniferous trees keep their needles throughout all seasons, and deciduous trees shed their leaves yearly each fall. Pine, juniper, spruce, and cedar go into the coniferous bucket. Maple, oak, birch, and ash go into the deciduous pail.

Yet knowledge is a tenuous thing. All our categories blur at some point.

Like the twin coniferous trees I discovered in a neighbor’s yard this past October. As the weather cooled, their needles shifted from bright green to golden brown before molting entirely. I thought they were dying.

Shorn of those spiky cloaks, now blanketing the ground, their limbs stood bare save for a few bulbous cones. As it turns out, these two supposed coniferous trees were in fact Dawn Redwoods, a deciduous coniferous blend of both categories. Wearing needles, they also habitually shed in the autumn.

Instead of dying, these Redwoods were fulfilling a cycle of regeneration.

Even more astounding, scientists had thought the Dawn Redwood had been extinct for millions of years. That is, until 1944, when someone stumbled upon this ancient and supposedly vanished tree thriving within the valleys of China’s Sichuan province.

The moral: We can attempt to understand the world and claim knowledge of it. But even our knowledge might fail us.

What we think we know today could turn out to be an error tomorrow. Each generation laughs at the follies of previous generations, believing in the veracity of their own claims to truth. But knowledge is rarely as stable and clear as we want it to be.

Yet, regardless of the quality or quantity of our knowledge about the world, this material place is where we, embodied creatures, live, breath, move, feel, and die. Unlike René Descartes’ postulation, we are not separate observers of the natural world, although, of course, our ability to observe is part of our brilliance. We are knit within the fabric of the universe, and we try to make sense of it, and ourselves, from within its folds.

And so, with “This” and “Domain” in “This Immanent Domain,” I hope to gesture toward our universe’s “whatness,” our observations of it, and the givenness of being.

Immanence

But what about “Immanent” in the title?

Immanence is a theological concept that refers to God’s presence within the created world. It goes beyond our competencies and knowledge, beyond our instruments, data, and scientific processes to the miracle of life itself.

Our experience of that immanent presence, I believe, is defined most of all by wonder.

We can also experience it as an often-intangible yearning for truth or beauty beyond ourselves, our comprehension, and even our articulation. It is the “what” that is unpossessable, and the “why” that is unquantifiable. You cannot categorize the immanent in spreadsheets, or map its traits on a graph. You can, however, note its chart across the horizon of your capacity to marvel and even worship.

Material signs

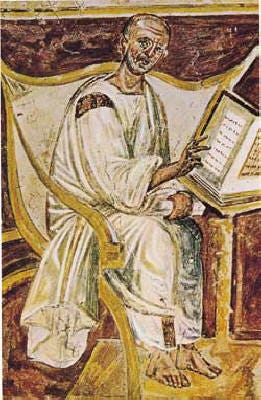

Ancient Christians, like St. Augustine of Hippo, saw the material world as a realm of signs directing the observer to that immanence within and behind creation, that presence.

For them, the material world and everything in it was created intentionally, ex nihilo, out of nothing, by a God beyond all things and yet permeating all things. In other words, the material world was loved into being and deemed good, “very good” (Gen. 1.31) by the very being of a transcendent God.

Perhaps due to that transcendence, the material and spiritual have often been perceived dualistically, set at polar extremes by non-religious and religious alike, Christians included.

However, it seems to me, without falling into pantheism or panentheism, rather than polarity, Christianity urges union. Transcendent God creates. Transcendent God becomes immanent creature, Immanuel, God with us. It claims a perspective in which material existence speaks to the indwelling presence of God.

Another way to say it: our spiritual journeys are not antithetical to our material lives. Instead, the spiritual intersects with the material at all its junctures.

“To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour”

- William Blake

I hope this newsletter can be a space to explore these ideas and especially our experiences – what it means to experience the material world and ourselves, and to view that world as a wonder, shot through and glowing with the presence of God.

Thank you for reading. More next time.

All good things,

Rachel